[177.2]

QUESTIONING BARENBOIM

In the aftermath of his first lecture (see my blog below), Daniel Barenboim responded to a range of questions from audience members at the Cadogan Hall in West London.The politician and pundit

David Mellor asked about music as a way of changing the world, not just understanding it. How is that going, and how would we measure its progress, he asked?

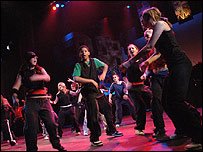

Responding with specific

reference to the East-West Divan Orchestra [pictured], composed of young Israelis and Palestinians, Barenboim talked of “the conditions of equality”, musical subversion and “listening to the other voices”. On its own a “utopian republic” of music is not enough. The “note of the enemy” must be heard and understood in terms of an alternative narrative. The work of the

East-West Divan Orchestra is not to give each other comfort but to understand the nature of music as an integrated system with its potential for re-situating difference.

Steve Martland (composer) enquired about the role of the living composer in this scenario. Barenboim replied, to laughter, “to write good music”. Today you write with the same 12 notes that every single composer before

Bach did. The power of music has nothing to do with contemporaneity. The difficulty today is that very few people practice music. (He illustrated this by playing

Schoenberg on the piano).

Julian Lloyd Webber (cellist) asked whether there was a danger of some educationalists assuming that because children are from certain ethnic backgrounds – say in inner city schools - somehow classical music is not for them? Naturally Barenboim agreed that this would be a foolish thing, referring to his own experience of breaking boundaries on the West Bank.

Willard White (bass) spoke about compulsion and voluntarism in relation to music education. The response was that it is not a matter of free will, but about offering a grounding which makes proper decision-making possible. “First you have to know about it.”

Asked by a researcher “how far down” he considers musical value to extend, Daniel Barenboim suggested that knowledge (understanding) is the distinguishing issue. In some cases little is required, the response is instinctual. But often guidance is needed to “live” the music. He contrasted a waltz or popular song with the complexities of Schoenberg.

Presenter

Sue Lawley interjected: “Do you accept then, Daniel Barenboim, that, that, that pop music can have that same transcendental power that you were describing that Western classical music has?”

The mercurial reply, at once humorous, generous and highly directional, was…

“If you feel it, how wonderful for you!”

Well-known (and classically trained) Jazz pianist

Julian Joseph asked about the role of improvisation in the process of music as Barenboim is expounding it – and was told, presumably to his agreement, that it is the highest form of artistic expression, an unpremeditated but dedicated state of consciousness.

Lesley Garrett (soprano) talked about her children’s bombardment with images, and asked how they could be guided to really hear sound. She was told that the situation was worse than this – in our culture we are anaesthetised against music through the musak that permeates of society at large.

“In English you have this wonderful difference between listening and hearing, and that you can hear without listening, and you can listen and not hear. Not every language has that.”So, Garrett responded, does that make opera the ultimate art form, a perfect unity of the visual and the aural? “Nonsense! In opera people look but don’t listen!” (laughter).

Neuroscientist

Lloyd Parsons said that his research indicated that the performance of music effected within the brain a distinction between mental processing and emotional awareness, say through the rendition of Bach. Some areas of the brain were activated, others not. Barenboim declared that in music you can control, for a moment, time – and also the life and death of a note. In this there is a sense of transcendence on a journey which is, in a way, longer than the temporality of a human being.

“You can control life and death of the sound, and if you imbue every note with a human quality, when that note dies it is exactly that, it is a feeling of death. And therefore through that experience you transcend any emotions that you can have in their life, and in a way you control time. I mean, we all know that when we are born, two minutes seem like two hours. And when we're interested, two hours are two seconds.”

James Macmillan

James Macmillan (composer) referred to

Julian Johnson’s controversial and provocative book

‘Who Needs Classical Music?’ He asked whether it was its ability to rise above the mundane, to evoke the possibility of a secret irreducible to commonality, and the illustrate the fact that the universe is not a closed system which lies at the heart of the refusal of ‘serious’ music in a debased culture? Barenboim declared his determination to resist the moralising of music in the discourse of elitism and anti-elitism. Music is innocent, but imbued. He then talked about the orchestra as the natural forum for discovering democracy – though not democratic in its own right.

“[T]he human being is not courageous by nature, and the human being always likes to blame something else - somebody else or something else - and therefore [s/he] says classical music is elitist, classical music is transcendent. I'm sorry, classical is none of that, classical music is nothing until it comes into contact with a human being.”A music therapist,

Alison Levine, asked about “the early stage of how we are in music”. Children, said the conductor, after some repartee about child prodigies, learn more discipline from rhythm than from being ordered around. The first associations with sensuality come through realising that passion and discipline need each other in musical experience. “We have to make music and we have to teach our children from the beginning the connection between music and life.”

An aside followed on music and political process, in which

Barenboim’s dialogues with the late lamented

Edward Said (specifically on Israel-Palestine and the Oslo process) were, unlikely though it seems, paralleled with issues in the performance of

Beethoven’s Pathetique – producing a kind of cross-disciplinary interpretative dissonance, giving way to fresh perceptions of harmonic possibility in different realms. Well, that’s how I’m hearing it. The transcript and podcast will enlighten further.

A brave psychologist concluded by asking what Daniel Barenboim would play if he had one minute to live, and would he play it now…? To laughter and with momentary bemusement, Barenboim responded by saying that he preferred

“to play every concert as if it was both the first and the last.” Comment on this post: NewFrontEars

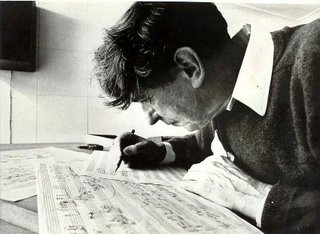

A bit outside the usual musical territory of NFE, but I was pleased that former Procul Harum keyboard player Matthew Fisher today won a share in the copyright and royalties of 'A Whiter Shade Of Pale'. It's a great song - an intriguing blend of ballad, Bach and lyrical psychedelia with a fine Hammond M-102 drawbar / Leslie cabinet sound (not the B3, as is often assumed). Fortunately the adjudicator, Justice Blackburne, read music as well as law at Cambridge.To prove his point Fisher [pictured] led the court through what the Daily Telegraph described "a dizzying 40 minutes of bar by bar analysis, picking out quavers, sequences, ascending and descending scales and dissonances." Good on him.

A bit outside the usual musical territory of NFE, but I was pleased that former Procul Harum keyboard player Matthew Fisher today won a share in the copyright and royalties of 'A Whiter Shade Of Pale'. It's a great song - an intriguing blend of ballad, Bach and lyrical psychedelia with a fine Hammond M-102 drawbar / Leslie cabinet sound (not the B3, as is often assumed). Fortunately the adjudicator, Justice Blackburne, read music as well as law at Cambridge.To prove his point Fisher [pictured] led the court through what the Daily Telegraph described "a dizzying 40 minutes of bar by bar analysis, picking out quavers, sequences, ascending and descending scales and dissonances." Good on him.